Important Facts About Stage 3 of Stroke Recovery

Swedish occupational and physical therapist Signe Brunnstrom was an important figure in advancing our understanding about restoring motor skills in stroke patients. Based on different limb synergies, she devised a way to organize stroke survivors into categories or stages of recovery.

Her method, the Brunnstrom Approach, involves seven stages of stroke recovery, the Brunnstrom Stages, that break down how stroke patients can regain motor control throughout their bodies. Muscle movements normally come from different muscle groups working together. Researchers refer to these patterns of activity as synergies. The brain is in charge of coordinating these movements, and a stroke can moderately or severely damage them. The Brunnstrom Stages were developed at the same time as protocols for interventions that relate to each stage.

Brunnstrom’s groupings have shaped research in occupational and physical therapy and have been helpful to describe a broad range of the motor pathology after stroke. Today, we’ll focus on stage 3 of the Brunnstrom Approach.

What Happens During Stage 3?

Spasticity in muscles increases during the third stage, reaching its peak. This is also when synergy patterns and the start of minimal voluntary movements begin to appear. These movements will be small and mostly abnormal.

Any increase in voluntary movement comes from being able to initiate movement in the muscle, though it can’t yet be controlled. The appearance of synergy patterns and coordination of muscles enable the voluntary movements that become stronger with regular physical and occupational therapy.

What is Spasticity?

Spasticity (from Greek spasmos–, meaning drawing or pulling) is a feeling of unusually stiff, tight, or pulled muscles. It is caused by damage to nerve pathways within the brain or spinal cord from a stroke that control muscle movement. The lack of ability to restrict the brain’s motor neurons causes muscles to contract too often. Spasticity causes an abnormal increase in muscle stiffness and tone that can interfere with movement, speech, or cause discomfort and pain.

What is Synergy?

Muscle synergies result from muscles coordinating movements to perform different tasks. These synergies allow common patterns of movement that involve either cooperative or reciprocal activation of muscle. The combined effects of several synergies lead to natural motor behaviors.

To understand muscle synergies, it is important to treat sensory and motor systems separately because both can change the pattern of how movement is initiated. The sensory system relates to signals that come from receptors in the skin, muscles, joints, and tendons that relay information about the outside world. An obstacle encountered during a walk is one example.

On the other hand, the motor system refers to the pattern of muscle activity. Thinking again of walking, the motor system reflects the simple movement patterns of a walking style, while other muscle groups respond to additional tasks, like stepping over obstacles.

Synergy & Stroke

After a stroke, these key motor pathways are damaged, and so synergies change. This typically happens on 1 side of the body causing hemiparesis. It is typical to also see that activity in one muscle may coincide with the inactivity in another due to this new reciprocal inhibition in muscle synergies.

In stages 2 and 3 of stroke recovery, abnormal flexor and extensor muscle synergies are common. Flexor synergy includes the external rotation of the shoulder, flexion of the elbow, and supination of the forearm. The extensor synergy, in contrast, includes internal rotation of the shoulder with elbow extension and pronation of the forearm. Both lead to poor movement and decreased range of motion so therapists will typically work with you on these to improve these synergies back to normal.

Therapists aim to identify absent synergies, or synergies that lead to poor movement, so they can recommend specific tasks to target these areas during rehab.

What Are Voluntary Movements?

All voluntary movements involve the brain, which sends out the motor impulses that control movement. These motor signals are initiated by thought and must also involve a response to sensory stimuli. The sensory stimuli that trigger voluntary responses are dealt with in many parts of the brain.

Voluntary movements are purposeful and goal directed. They are learned movements that improve with repetition or practice and require less attention. Some examples include combing hair, swinging a bat, driving a car, swimming, and using eating utensils.

During this 3rd stage of stroke recovery, you start to get more of these impulses and triggers back. This allows you to start to get back to normal life and activities like cutting your food.

Possible Treatments for Spasticity and Increasing Voluntary Movements

After a stroke, hemiparesis, or weakness of one entire side of the body, is common. Impaired upper limbs are seen in 75 percent of stroke patients. Therefore, recovering the affected side of your body as well as upper-limb function is an important goal during rehab.

Muscles with severe spasticity, like the ones in stage 3 of stroke recovery, are likely to be more limited in their ability to exercise and may require help to do this. Patients and family/caregivers should be educated about the importance of maintaining range of motion and doing daily exercises. It is important to minimize highly stressful activities this early in training.

Therapists and patients can follow a general treatment guideline involving:

- Contracting 1 muscle while the other one relaxes. These are performed first in small ranges and progress to larger arcs of movement.

- Lengthening of spastic muscles.

- Attempt to contract muscles reciprocally (biceps and triceps).

- Targeting functional skills for training.

- Educating patients and family/caregivers about the importance of maintaining range of motion and doing daily exercises.

Sensory Exercises

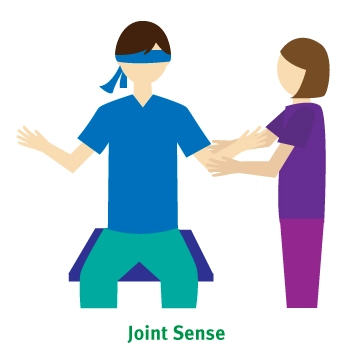

Joint Sense

The patient is seated and blindfolded. The affected upper limb is supported by the examiner and moved to different positions while the patient is asked to perform identical position with the unaffected extremity.

Touch Sensation

The palmar aspect of fingertips (pads) are touched with the rubber end of a pencil, and the patient is asked to determine without looking which fingertip is touched.

Sole Sensation

The patient, without looking, is asked to determine if an object is touching and pressing against the sole of their foot or not, and where.

Passive Range-of-Motion Exercises and Stretching

Passive exercises, also known as passive range-of-motion (PROM) exercises, should be continued during this stage to improve your range of motion. Treatment includes how far the therapist can move your joints in different directions, like raising your hand over your head or bending your knee toward your chest.

These exercises are considered passive because you don’t exert any effort. Someone like your occupational therapist, physical therapist, or rehabilitation nurse helps you move your muscles and joints through their full range of motion.

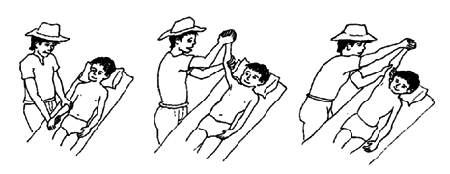

An example of this:

Passive Forearm Supination and Pronation

The therapist sits in front of the patient and pulls thumb out of palm. They passively rotate the forearm alternating supination and pronation (palm up/palm down).

These exercises help prevent joint contractures and maintain joint flexibility. They also help take you through the movements so you can start recognizing isolated joint movement outside of synergy. This will help you start these motions voluntarily. Check out Physio Therapy Exercises for helpful how-tos and pictures of passive range-of-motion exercises you can do.

Active Range-of-Motion Exercises

Active range-of-motion exercises can be used to assess spasticity during any one of the recovery stages as long as you have sufficient active range of motion. Active range-of-motion exercises (AROM) help improve joint function and increase synergy recognition to allow you to get on your way to full voluntary movements.

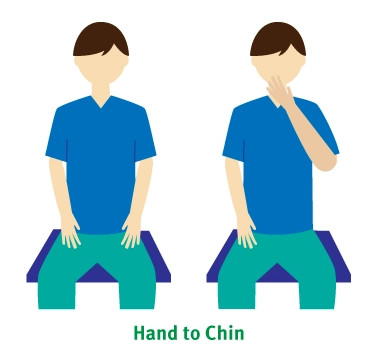

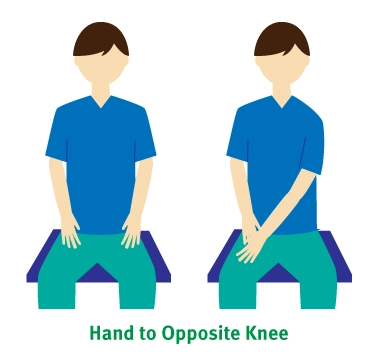

Examples are:

Hand to Chin: The patient is seated on a chair without an armrest, leaning against the chair’s back and keeping their head erect. The hand is moved from lap to chin, requiring complete range of elbow flexion. With this movement, try to keep the affected elbow at the side of the body to foster isolated movements.

Hand to Opposite Knee: Another exercise is moving the hand from lap to opposite knee, requiring full range of elbow extension.

These range-of-motion exercises can be recorded for time, and the faster they are performed, the more progress is made with recovery and reducing spasticity.

Stroke Recovery Gloves

Like splints, dynamic gloves can also help during stage 3 of stroke recovery. Stroke recovery gloves such as the SaeboFlex and other rehabilitative dynamic splints help imitate the hand’s natural functions—making it possible to grasp and release objects. This helps build strength and reduce spasticity in your hand and arm. Using helpful devices like this gets you well on your way to performing everyday activities voluntarily.

Balancing and Sitting

Facilitation by a therapist is reduced as the patient shows voluntary control of balance and sitting positions. By the end of this stage, you should be able to fully balance and sit by yourself.

Here’s an exercise to help assess how your balance is:

Trunk Balance in Sitting: The patient is asked to assume a sitting position, lifting the affected upper extremity by the unaffected one. The patient then actively performs trunk movements in all directions.

Moving on to Full Voluntary Control

Stage 3 might be the most painful stage to get over as spasticity in muscles reaches its peak. The good news is synergy patterns also start to emerge, and minimal voluntary movements are starting and further developing. Focusing on these synergies and developing them into full voluntary movements into stage 4 of stroke recovery allows you to begin to regain a significant amount of motor control in your affected extremities.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. Reliance on any information provided by the Saebo website is solely at your own risk.